Racial Justice

The Need to Decolonise Higher Education

Read a summary or generate practice questions using the INOMICS AI tool

History, it feels, is quickening pace. Pandemics, both old and new, are rocking the world, shaking its foundations. Systemic racism, an age-old disease, continues to facilitate violence on black bodies and undermine humanity, while a novel coronavirus has killed hundreds of thousands, disproportionately affected people of colour, and compounded the often racial inequalities that characterise our societies. Protestors now fill the streets, and across much of the anglophone world a tipping point has been reached. What will emerge from this moment is hard to say. A better question may be what do we want to emerge? Either way, there can be little doubt, change is afoot - and it’s been a long time coming.

Education is complicit

Education is complicit

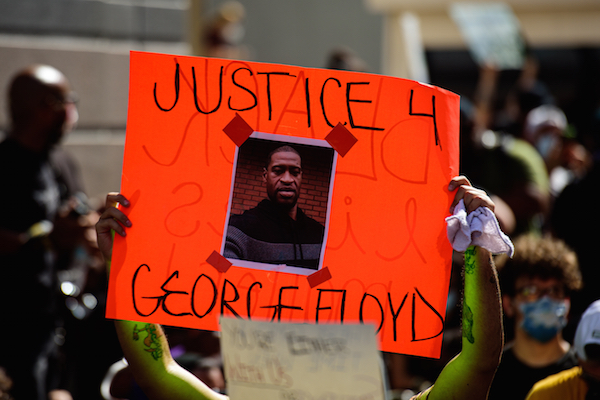

Education is one area that could be subject to overhaul. The recent murder in America of George Floyd at the hands of Minnesotan police has sparked demonstrations across the western world, protesting not just police violence, but the system that permits such violence and ensures impunity for its perpetrators. Education, protestors claim (and this writer concurs), is a part of that system, and higher education, in particular, has drawn criticism for its failure to incorporate black and brown histories, focusing instead on white, euro-centric knowledge and methods of knowledge production. These preferences, they further assert, hide the achievements of people of colour, perpetuating hierarchies of colonialism. Ultimately, this omission, and the whitewashing of colonial violence for which it also stands accused, implicates the institution as complicit in the racism that pervades society. As such, if progress is to be made it must be ‘decolonised’.

Work underway

Of course, work to this end isn’t new. In the last few years, demands to decolonise education, both its curricula and campuses, have cohered into the movements ‘Rhodes Must Fall’, which has called for the removal of statues of the imperialist Cecil Rhodes from campuses, and ‘Why Is My Curriculum White?’, which, as the name suggests, has questioned the primacy of white, European thinkers in university curricula. Both have helped expand conversations about memorialisation in public space and the diversification of education, setting some important precedents. Now, however, as racism is reckoned with on both sides of the Atlantic, movements like these have been galvanised. And the momentum is only growing.

Suggested Opportunities

- Summer School

- Posted 1 day ago

BSE Summer School 2024: Economics, Finance, Data Science, and related fields

Starts 17 Jun at Barcelona School of Economics in Barcelona, Spain

- Conference

- (Partially Online)

- Posted 11 hours ago

Annual Research Conference 2024

Between 21 Nov and 22 Nov in Ispra, ItalyWhat is being asked?

Although decolonising education can, and often does, mean different things, it generally refers to an interrogation of the assumptions that form the basis of the canon, and an attempt to broaden our intellectual vision to include a wider range of, in this case non-white perspectives. It questions: who’s in control of knowledge? How did they come to have this role? And what maintains their power? Indeed, in many ways its goal aligns with the professed ethics of academia itself: to enhance both our critical thinking and scepticism.

Key is the recognition that colonial assumptions regarding racial hierarchy persist in academic study. SOAS University of London, for instance, an institution embracing its responsibility to modernise, has pointed to the fact that despite no longer referring to countries in the global south as ‘backward’, many theories of development rely on similarly unfavourable assumptions for their modelling - it’s these biases the decolonising process looks to address, and they’re pervasive.

It also questions the relationship between the writers of knowledge, their location and identity, and the subject of their work and method of investigation. This sounds commonsensical because it is - it already takes place in many other contexts. For example, as a society we’ve grown instinctively scrutinous of male voices explaining away the female experience, and for good reason. Decolonising education asks for an extension of this same principle with respect to race.

Assess the origins of source material and another problem is encountered: reading lists are composed overwhelmingly of white, male authors. This not only marginalises much excellent scholarship produced by scholars of colour, but also introduces, as academic James Muldoon has described, ‘systematic distortion to the material’. Moreover, it creates a phony impression of who constitutes intellectual authority and what works are worthy of our attention. To counter this deficit, decolonisation would diversify the sources engaged with to reflect a greater variety of perspectives .

Finally, action is called upon to guarantee a university environment that addresses the attainment gap between people of colour and their white colleagues. With society wracked by structural inequalities, now compounded by COVID, it's imperative for educators to ensure students receive equal opportunity to succeed. This means defining and dealing with the racism that is woven into all aspects of university life. When students of colour report feeling alienated by certain learning materials, or dynamics in the classroom, it must be dealt with through open dialogue between students and educators, and followed by swift action. With surveys consistently showing African American undergraduates as having the lowest satisfaction rates of all students, it appears these pastoral responsibilities are currently being neglected.

The pushback

Despite its ethical grounding, moves to decolonise higher education have not been without controversy, attracting a sizable backlash. In the UK, for instance, Conservative politician Sam Gyimah warned that we “should be cautious of … phasing out parts of the curriculum that just happen to be unpopular or unfashionable’, his comments coming in response to English students at the University of Cambridge calling for the inclusion of more non-white writers and postcolonial thought in their syllabus. And this is a common response, calls for increased inclusivity misconstrued as moves towards eradication, of scrapping everything.

In reality, no one is seeking the abolition of the canon, or the complete elimination of any white male influence from centres of learning. The game is not zero-sum. People simply want their educational systems to better reflect society, to generate more accurate portrayals of our histories, and to accept and rectify the implicit, and at times explicit, biases that as institutions they continue to perpetuate.

Alas, even in this revolutionary moment, the barometer of change shows that this battle will be hard won - at the time of writing only a fifth of UK universities have formally committed to reforming their curricula to confront the harmful legacy of colonialism. Nonetheless, there is reason for optimism: pressure continues to build. The Black Lives Matter movement has proven the effectiveness of direct action and the power of mass movements. The toppling of the statue of slaver Edward Colston in Bristol has forced a review of all London street names and landmarks, in a move that will only invigorate protestors. And with higher education now in their sights, universities may be in for the shake up they so desperately need.

-

- Supplementary Course

- (Online)

- Posted 4 years ago

The History of Economic Thought

at University of Oxford in United Kingdom -

- Professional Training Course

- (Online)

- Posted 4 years ago

Macroeconomics: An Introduction

at University of Oxford in United Kingdom -

- Conference

- Posted 7 months ago

2nd world Conference on Data Science & Statistics (Data Science Week 2024)

Between 17 Jun and 19 Jun in Amsterdam, Netherlands