A Heavyweight Clash

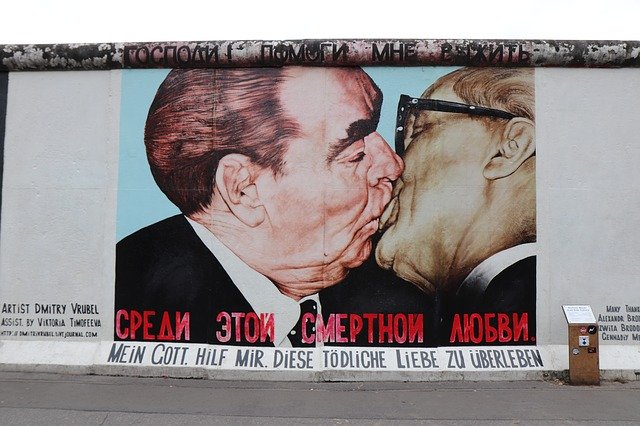

Capitalism vs Socialism

Read a summary using the INOMICS AI tool

As claims go, Francis Fukuyama’s insistence that history’s run its course has aged rather badly. The ascent of China, the Great Recession, spiralling inequality across the West, and now COVID-19, have all, in their own way, undermined his notion that capitalist liberal democracy is the political endgame. If anything, political choice seems to be expanding. People are increasingly being offered the opportunity to continue with capitalism, occasionally of the nativist variety and sometimes strictly neoliberal, or, alternatively, to try a little socialism.

However simple sounding this choice may be, the question is, in fact, a tricky one. What’s even meant by each term? In the current polarised political climate, where both are bandied about and often weaponised, definitions have blurred. Deplorable in the eyes of some, the roadmap to utopia to others. Many are understandably confused. What should one make of being branded a champagne-sipping socialist? Or a capitalist pig? To make sense of it all, we have delineated each term as concisely as possible. Meaning next time the political barbs start flying, you will at least know how offended to be when one comes your way.

Suggested Opportunities

- Conference

- Posted 2 days ago

46th RSEP International Conference on Economics, Finance and Business

Between 17 Apr and 18 Apr in Paris, France

- Summer School

- Posted 1 week ago

BSE Summer School 2026: Economics, Finance, Data Science, and related fields

Starts 22 Jun at Barcelona School of Economics in Barcelona, Spain

Capitalism

Of the myriad differences that distinguish capitalism from socialism it’s the level of government involvement in the economy that’s most fundamental. The capitalist model is premised on the private ownership of the means of production and property. The economy relies on open, free markets whose forces - the so-called ‘invisible hand’ - determine prices, incomes, wealth and the distribution of goods. In theory, unencumbered competition then drives innovation - in technology and practice - and encourages companies to make the best products they can as cheaply as possible. Over time, therefore, products improve in quality, while becoming cheaper. ‘Inefficient’ companies that fail to keep up, as in, their products are relatively expensive or poor in quality, are quickly usurped and go out of business. This allows resources to flow to other, more ‘efficient’ areas - a process Joseph Schumpeter called ‘creative destruction’. Meanwhile, the consumer is ensured maximum choice at the minimum price - again, in theory at least.

And this is what lies at capitalism’s heart: the promise of meritocracy, of efficiency winning out. It underpins the whole system. This leads neatly to another key distinction from socialism: equality, or, in capitalism’s case, the lack thereof. Under capitalism, inequality is essential. It serves as a driving force, incentivising work with the lure of what could be. The spoils are there, you just need a good work ethic and the right ideas. And who decides which ideas are right? The market. It’s this cold, unbiased mechanism of relentless wheat-from-chaff-separation that drives economic development and moves us forward.

Socialism

A socialist economy, on the other hand, is driven by a vastly different logic. Through greater governmental intervention, it seeks to (re) allocate resources in a more egalitarian way. In part, this is ensured by state ownership– as opposed to individual– of the major means of production. As the main employer, the state can then determine wages, working hours, and preserve a certain standard of working conditions as it sees fit. Employment rates, thus, are not vulnerable to spasms of the market, meaning full employment can be guaranteed - in some socialist societies that is. In others, individual ownership of property and enterprise is permitted, but is accompanied by high taxes, especially on the rich, and tighter, more stringent government control, to help avoid exploitative practices from developing. To purists, this is no longer socialism, but rather a form of social democracy. In America, it’s tyranny.

Where capitalism favours efficiency, socialism focuses on equality, a channeling of wealth from the rich to the poor, and the establishment and preservation of an even playing field - definitely in opportunity, and occasionally in outcome. This is achieved by various means including the state-led provision of healthcare, free at the point of use, price controls, higher taxes, and far more spending on public services.

In practice

In reality, most countries - even the US, the paragon of capitalist life - operate mixed economies, that is with economic elements of both capitalism and socialism. Therefore, the question playing out around the world is less a choice of one or the other, but more nuanced. Typically, it’s the pitting of greater public provision, in the form of healthcare, education and social security, typically funded by higher taxes (i.e socialist inclined policy), against tax cuts and a general retreat of the state out of the individual’s life (i.e free-market capitalist inclined policy). It's notable that in the majority of cases these proposals are made while accepting an overarching capitalist system. The extremes may be tweaked, but the fundamentals are normally left unquestioned.

-

- Postdoc Job

- Posted 2 weeks ago

Research Assistant (Postdoctoral Fellow) (f/m/d)

At University of Bremen in Bremen, Germany

-

- Assistant Professor / Lecturer Job

- Posted 1 week ago

Assistant Professor of Economics (tenure-track)

At University of São Paulo in São Paulo, Brazil

-

- Conference

- Posted 1 week ago

Macroeconomic Policy in a Heterogeneous and Imperfectly Rational World - 6th Joint NBP-LB-CEBRA Biennial Conference

Between 24 Sep and 25 Sep in Warsaw, Poland