Political Thought

A Critique of Neoliberalism

Read a summary using the INOMICS AI tool

Few would contest it as the ideology of our political age. Ever since the 1980s, it has dominated western politics, underpinning governance, influencing culture, and leaving its indelible mark across society. During this time its core tenets were rarely challenged and only its peripheral aspects tweaked.

The 2008 financial crash, however, changed this, shaking confidence in an ideology whose name, up until that point, was rarely ever spoken. With the loss of savings, skyrocketing inequality and falling living standards that followed, people wanted answers and began to question the political system that had facilitated such a disaster.

Although over a decade later neoliberalism is yet to be replaced, its grip on power has considerably loosened, the pandemic – and all its attendant injustice – forcing the most recent reckoning with its shortcomings. It’s a process we can see in real time, with new political formations emerging on both the right and left. Indeed, alternatives that in previous years would have been dismissed as too radical, utopian or even regressive, are now earnestly discussed as people seek an exit from the current political model.

But what does this really mean? What exactly are these alternatives looking to depart? The word neoliberalism is used with such regularity – and at times carelessness – that its definition has become hazy, its precepts unclear. And therein lies much of its power.

To escape its clutches people must first understand it: how it arose, to whom it accrues power, and by what means it has been sustained. To that end, the following attempts to dissect the term, studying its history, the policies born from its logic, and the effects it’s had on society.

It's conception

It's conception

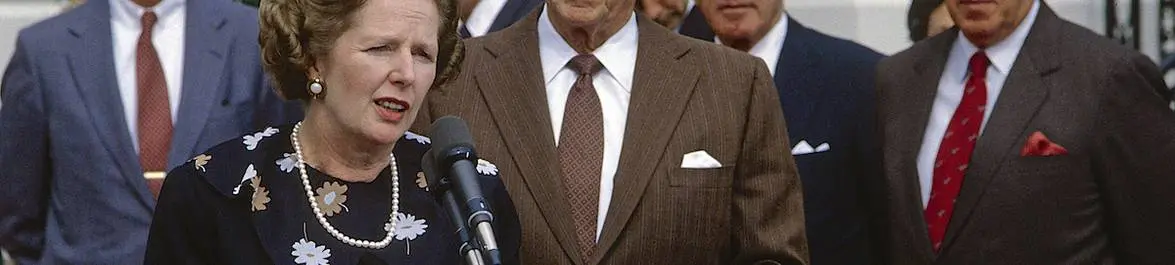

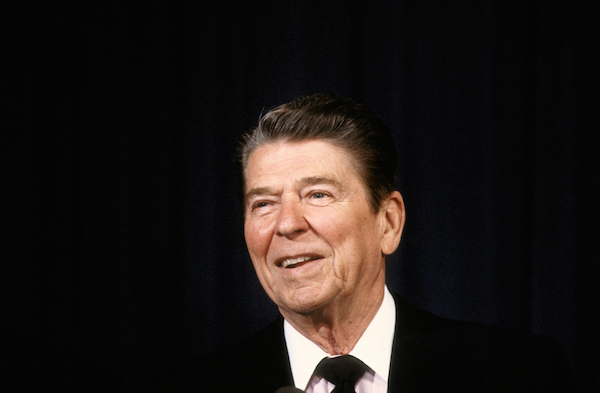

Although famously associated with the politics of Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan, neoliberalism’s history predates both leaders – the term likely first used in the late 19th century. It found an institutional home, however, some fifty years later, when in 1947 a group of alarmed economists convened at Mont Pelerin, and ominously warned that ‘the essential conditions of human dignity and freedom had disappeared’.

To those in attendance – who would coalesce and become the Mont Pelerin Society – the roots of the crisis were clear and found in the ‘declining belief in private property and the competitive market’. A staunch defense of an increasingly besieged free-market capitalism was needed, and the state must withdraw from interfering with economic activity – only then could liberty be preserved.

This fear of state intervention was so potent it placed social democracy on the same spectrum as both Nazism and communism. By this logic, government planning – whether in the United State’s New Deal, or the UK’s nascent welfare state – was something to be fought and a mortal danger to individualism, another of the Society's key tenets. State intervention of any kind, it was believed, could, and likely would, lead to totalitarian rule.

While hyperbolic to a modern ear, one should remember the period in which these schools of thought emerged. Friedrich Hayek’s polemic The Road to Serfdom – considered a founding text of the doctrine - was first published in 1944 as the Second World War still raged and people were seeing first hand the horrific potential of total state control.

Hayek identified German and Soviet economic planning as the birthplace of these tyrannies and promulgated economic libertarianism, a serious reduction of governmental intervention into the economy, as the most effective bulwark against such abuses.

As the century progressed, the fledgling ideology caught the attention of the rich who saw it as a means of escaping unwanted governmental restraints – in particular, public protections and high taxation. Through lavish funding from these elites, a network of think tanks straddling both sides of the Atlantic was quickly established, designed to spread the neoliberal word among academics and policy-makers.

Despite this financial backing, the ideology remained on the margins. The post-war consensus was in full swing and Keynes’ economic recommendations were being readily applied across most of the Western world. Governments were unashamedly raising taxes – in the UK income tax reached 75% – broadening public services and expanding social security. Neoliberals, in contrast, were thought of as out of step with the real world, relics from the past, and were forced to bide their time.

It wasn’t until the economic crises of the 1970s that neoliberalism finally got its chance. But when it did, its ecosystem of think tanks, pressure groups, and organizations were well prepared. As its influential proponent Milton Friedman commented of the time, when Keynesian economics began to fail, and people were scrambling for change, ‘there was an alternative ready there to be picked up’. The world has not looked back.

Suggested Opportunities

- Summer School

- Posted 2 days ago

Global School in Empirical Research Methods GSERM at the University of St.Gallen

Starts 20 Apr at University of St.Gallen in Sankt Gallen, Schweiz

- Konferenz

- Posted 1 week ago

46th RSEP International Conference on Economics, Finance and Business

Between 17 Apr and 18 Apr in Paris, Frankreich

The policies

Most famously, neoliberal prescriptions were ‘picked up’ by Thatcher and Reagan who assumed power in 1979 and 1980 respectively. Thatcher was a self-professed, dyed-in-the-wool neoliberal. And had it not been for the reluctance of her own cabinet she would have carried out Hayek’s doctrines to the letter - recently released letters show she had hopes of dismantling the entire welfare state.

As it was, in her 11 years as Prime Minister she was still capable of transforming British society. Through a neoliberal policy program of massive tax cuts for the rich; a drawn out, but eventual crushing of trade unions; widespread privatization of housing, telecoms, steel, and gas; financial deregulation; and the introduction of competition in the provision of public services; she left Britain a markedly different place.

Across the pond, Reagan had embarked on a similar journey, gutting union power and cutting government spending. Capturing the spirit of the age he declared that ‘the most important cause of our economic problems has been the government itself’. It wasn’t long before the ideology was also adopted by international institutions like the IMF, World Bank and World Trade Organisation, and imposed on an unprecedented scale across the world.

Its spread was such that even nominally left-wing political parties, like the UK Labour Party and the Democrats in America, would eventually cave into its practices, assimilating its core principles. And with that, the ‘Overton window’, the range of ideas tolerated in public discourse, moved someway to the right.

The reality

The politics of the 1980s were, without doubt, neoliberalism at its most strident, and its record during the time is highly contested. In Britain, where its tenets were most closely followed, policy aims were often missed. Economic growth – the Holy Grail to neoliberals and a chief indicator of progress – was actually slower than in previous decades, and its dividends were increasingly unevenly distributed – inequality dramatically rising.

Meanwhile, Thatcher’s smashing of the unions left workers vulnerable in the face of big business, and without the protection of collective action, wages were squeezed. This meant that even when the unemployment rate began to fall, in-work poverty rose.

Similar trends were found in the US where Reagan's massive tax cuts, shrinking of social security (food stamps, for instance, were slashed), and increased subsidies for corporations increased both inequality and poverty, while lining the pockets of big business. Already unequal, the balance of power tipped further away from the everyman.

It was also tipping away from the state. The wilful transfer of authority into the hands of unaccountable transnational corporations was perhaps an even greater consequence of the ideology’s supremacy. Important services were outsourced, the market left in charge, and, with the lobbying industry exploding, money began to rule the roost.

This development has proved a dangerous one, reducing governments' ability to respond to the needs of their electorates. Disempowerment and the perceived disconnect between the rulers and the ruled has in turn fed both disenfranchisement and volatility among populations. Few, for instance, would doubt that it was this culture, this feeling of impotency, that contributed both to Brexit and the election of Donald Trump.

More than just an economic theory

As it’s evolved, entrenched, and become normalized in public discourse neoliberalism has, like many sets of economic and political ideas, morphed into a more general framework by which we are encouraged to understand the world, ourselves, and why we behave as we do.

In its crowning achievement, it has managed to redefine what it means to be human. No longer the sentient, cooperative and empathetic beings scientific evidence suggests we are; humans have been reduced to competitors. Coldly rational – ruthless even – neoliberalism has set people against each other, valorising the notion of ‘getting ahead’ – the question of whom, and by what means, too infrequently asked.

Our democratic choices, it has also taught us, are best expressed in transaction: a process of rewarding merit and punishing inefficiency that no government could match. It has, in essence, encouraged atomisation. It has loosened societal ties, sanctifying the interests of the individual over all else. As Thatcher would memorably pronounce: ‘there is no such thing as society’.

Over time, too, these notions have been internalized, such that now the rich, ignoring their structural advantages of birthplace, inheritance and education, have come to believe that their success is merely a result of their own ability. The inverse is also true. The poor, instead of seeing the often insurmountable obstacles they face, have come to blame themselves for their debt, unemployment, or lack of health.

Because of these structural barriers, now so deep-rooted, social mobility has slowed, and wealth is increasingly concentrated in the hands of a few. On a personal level, the development of this unforgiving, dog-eat-dog culture has coincided with a proliferation of mental health conditions that populations are now experiencing on unprecedented levels. Self-harm, depression, anxiety have all become hallmarks of our modern age.

To fundamentalists this inequality, this inevitable by-product of neoliberalism, is considered virtuous, the talented and hardworking elevated above the idle and unskilled. The system, they contend, is the closest to fair that we can hope for. Taking a look around it’s difficult not to hope that they are wrong.

What's next?

Whether neoliberalism really is in its last throes hinges on a new system, based on new values, taking its place. And this is far from certain. Political imagination has, for some time, been in short supply. For decades, political parties have hovered around the center ground desperately triangulating in the hope of attracting weary, apathetic voters.

However, in the wake of the Brexit and Trump earthquakes, and the devastation of COVID, we may have reached some kind of juncture. As we survey the mounting dissatisfaction, inequality, and alienation, it's hard to argue that things are as they should be.

The question is: will something new emerge from the wreckage? Or will we return to a politics of tinkering around the edges, the politics that brought us here, and has, up until now, failed to address society's biggest problems. Only time will tell.

-

- Workshop

- Posted 1 week ago

Geopolitical Alignment, Tensions, and the Global Economy (Measurement and Evidence)

Between 4 Dec and 4 Dec in Nanterre, Frankreich -

- Konferenz

- Posted 1 week ago

Macroeconomic Policy in a Heterogeneous and Imperfectly Rational World - 6th Joint NBP-LB-CEBRA Biennial Conference

Between 24 Sep and 25 Sep in Warsaw, Polen

-

- Workshop

- Posted 1 week ago

Call for Papers. The Legacy of Adam Smith Workshop | 22 June 2026 | Edinburgh

22 Jun in Edinburgh, Großbritannien