Economics Terms A-Z

Unemployment

Read a summary or generate practice questions using the INOMICS AI tool

Being unemployed means that a person is seeking employment, but does not have a job. The unemployment rate is the proportion of the labor force that is unemployed and is a key macroeconomic metric that helps describe the health of an economy.

Low unemployment rates are associated with high levels of production and economic growth, and vice versa. High rates are associated with times of recession, and are consequently a key concern for economists and policy makers alike.

Defining the unemployment rate

Government departments of labor (or the equivalent in a given country) and the OECD calculate the unemployment rate based on labor force surveys. According to these surveys, a person is unemployed if he or she is of working age (i.e., aged 15 to 64), is without work, and is actively seeking employment. Similarly, a person is considered to be employed if they are aged 15 or above and worked for at least one hour in the week before taking part in the survey. Only paid work is included in the OECD definitions: there are different measures that include laborers working part-time as well.

The unemployment rate u is then calculated as the number of unemployed people relative to the labor force, where the labor force is the sum of employed and unemployed people:

u = (# of unemployed people / size of labor force) * 100.

Anyone without employment who is not actively searching for a job is not considered unemployed. This includes full-time students who are not working, persons who take care of household or childcare duties, and other people who may be productive but are not paid for their work.

Another group of people that aren’t counted as unemployed are so-called “discouraged workers”. These are workers who were previously unemployed but have stopped looking for work because they struggled to find a job and eventually stopped looking. Some countries may use other names for this group, such as “hidden unemployed”; and while most countries don’t include them in the official rate, most do track them. And, politicians or economists may advocate for changing the unemployed definition to include discouraged workers. Regardless, the existence of this group indicates that the unemployment rate – despite being an important indicator of the healthiness of the labor market – is not sufficient to fully describe the labor force.

Other indicators need to be taken into account as well. The labor force participation rate, for instance, measures the size of the labor force relative to the working age population, and therefore includes students, household laborers, discouraged workers, and more.

According to economic theory, there are different types of unemployment, and not all are equally worrisome.

- Frictional unemployment refers to people that are in between jobs or have just graduated and started looking for a job. It can never be eliminated entirely and is not usually concerning, because people that are temporarily unemployed while they transition from one job to another will not be out of work for long.

- Seasonal unemployment is caused by the seasonal nature of certain types of work, for instance, in the tourism or construction industries. This is considered normal as well.

- Cyclical unemployment is associated with the business cycle. During a recession, firms lower production and lay off workers, while during a boom, firms expand production and hire additional workers. Thus, when the economy is growing there will be fewer unemployed workers, and when contracting, there are more. This is concerning when a recession is severe or prolonged, but sometimes it just represents normal ebbing and flowing of economic activity.

- Structural unemployment arises when creative destruction makes certain jobs obsolete (usually from advancing technology). For example, professional scribes became obsolete after the invention of the printing press. New jobs are often created when technology advances, though; typists using printing presses and later computer keyboards gained jobs performing similar, but more efficient, functions as scribes once had. The more concerning employment issue that creative destruction causes is that retraining people who lost their jobs to take over the newly created ones can be difficult and costly, especially since they sometimes require entirely different skills. Therefore, structural unemployment often leads to people being unemployed for long periods, or dropping out of the labor force entirely as jobs for their obsolete skill set disappear.

- Institutional unemployment results from an absence of incentives for the unemployed to actively seek employment, among other factors. Generous benefits for the unemployed, for example, are thought to disincentivize people from searching for employment, whereas a high minimum wage may make it unattractive for firms to hire additional workers.

- When the economy is producing its maximum potential output, there’s still inevitably some number of unemployed workers. This is represented by the natural rate of unemployment, which is considered normal and unavoidable. The natural rate is found by adding the frictional and structural rates, and it can change over time due to structural changes.

A look at some real-world context

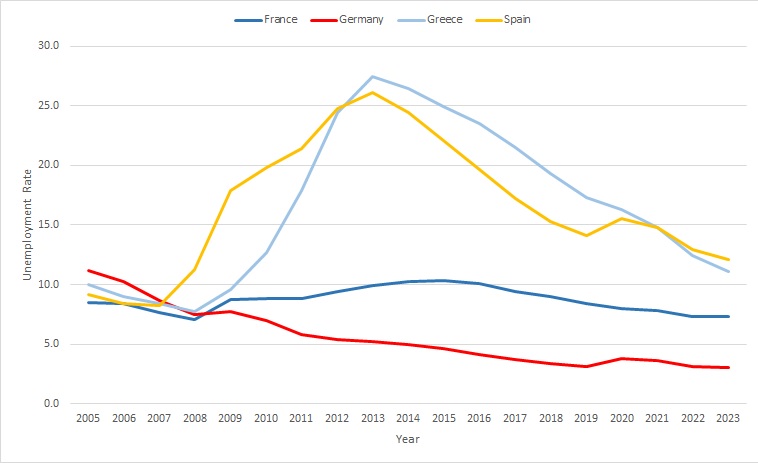

Let’s have a look at a few numbers from the European Union to get a sense of the unemployment rate in real economies. In Figure 1 we see these rates for four different European countries: Germany, Greece, France and Spain from 2005 until 2020 (Source: OECD).

Figure 1: Unemployment rate in select EU countries, 2005-2023 (OECD Data)

In Figure 1, Germany’s rate decreased until 2020, and starting from 2007 was always below 10%. France had a somewhat higher rate than Germany that rose steadily after the 2008-2009 financial crisis. It hovered around 10% before finally beginning to slowly decline in 2015. Spain and Greece, meanwhile, had rates which at times even exceeded 25%. This shows the dramatic effect that the financial crisis had on France, Spain and Greece in employment terms – while some countries like Germany seemed to fare much better.

This overview of Figure 1 naturally leads to the question: what is a “good” or “healthy” rate of unemployment? Various sources usually state that a healthy rate is somewhere between 3% to 6%, though there is no definite rule. Some economies may be healthy at higher or lower rates. And the rate is expected to fluctuate with the business cycle, even if it is considered healthy.

Nevertheless, it’s a cause for concern when the amount of unemployed workers in the economy remains high for a prolonged period, as is often the case during times of major recessions or depressions. Then, it often becomes a major target of fiscal and monetary policy as the government and central bank look for ways to stimulate the economy.

Further reading

Okun’s law refers to the relationship between employment in an economy and output growth. The economist Arthur Okun (1928-1980) stated that there is a negative relationship between them: for every 1 percentage point increase in the unemployment rate, the output of the country will shrink by 3 percentage points, according to Okun.

Studies have generally concluded that Okun’s law is directionally correct, though the exact magnitude of the effect varies considerably. Nevertheless, the idea is a sensible one. As more people work, ceteris paribus, the economy should produce more, and incomes should rise.

In “Okun’s Law: Theoretical Foundations and Revised Estimates” (The Review of Economics and Statistics, 1993), MFJ Prachowny shows that the output reduction associated with an increase in the unemployment rate is less severe when taking into account the output gap.

Good to know

Of course, unemployment rates can be compared not just across countries but also age groups. Usually, younger and older workers tend to be unemployed the most frequently.

This is because younger workers may choose to pursue further their education before (re-)entering the workforce, while older workers tend to be more affected by structural unemployment factors (as there has been more time for their skill sets to become obsolete or face lowered demand), among other factors.

When facing high unemployment rates, policy makers have to decide which public policies and measures are most suitable to the specific characteristics of the unemployed groups in their region. To this end, it’s important to look at a variety of demographic characteristics such as education, gender, age, and so on, as this can help inform which policy measures would be the most effective. Policies that aim to increase employment for youth will differ from measures targeted at increasing employment for seniors.

-

- Postdoc Job

- Posted 1 week ago

Postdoctoral Research Fellow - New Zealand Policy Research Institute

At Auckland University of Technology (AUT University) in Auckland, New Zealand

-

- Assistant Professor / Lecturer Job, Researcher / Analyst Job

- Posted 3 days ago

HEC Paris — Education-Track / Clinical Faculty Position in Family Business

At HEC Paris in Jouy-en-Josas, France

-

- Assistant Professor / Lecturer Job

- Posted 1 week ago

Lecturer/Senior Lecturer - Economics

At University of Otago in Dunedin, New Zealand