Economics Terms A-Z

Loanable Funds Market

Read a summary or generate practice questions using the INOMICS AI tool

The loanable funds market (also sometimes called the “market for loanable funds” in economics) is an important macroeconomic concept. Loanable funds are the most common way that major economic investments are funded, leading to long-term economic growth. It’s also an important concept because it shows one way that the (real) interest rate can be determined.

The market for loanable funds is a market that behaves similarly to a typical product market that students learn about in microeconomics, with supply and demand curves and all. In this case, the “product” is an amount of loanable funds. But what exactly are these funds, why are they important, and how do they help to determine the interest rate?

Defining loanable funds

Loanable funds are sums of money saved by lenders that are available for borrowers to use. When a firm or an individual wants to make a major investment, like upgrading the company’s manufacturing software or buying a house, they’ll usually need to take out a loan in order to afford the investment. These borrowers then seek a lender from whom they can take out a loan. In the modern economy, this process is usually aided by organizations like banks that help to connect savers and borrowers.

Like with any other market, there is a supply of savings that are available for borrowing – or in other words, loanable funds – and a demand for borrowing those funds. Equilibrium is normally determined where the quantity supplied and the quantity demanded of an item are equal to one another at a certain price. But what’s the price for a loan?

The answer is the interest rate. The interest rate on a loan determines the amount of money in addition to the loan’s original amount that the borrower must pay back to the lender when the debt comes due. So, the interest rate represents the price for the loan.

When many new borrowers start to demand loans, the price for borrowing will rise, meaning the interest rate will increase. But when there are more lenders than borrowers, lenders must reduce the price of the loanable funds they offer in order to compete for borrowers, lowering the interest rate.

The market for loanable funds can be graphed just like a market for a “typical” good or service.

Graphing the market for loanable funds

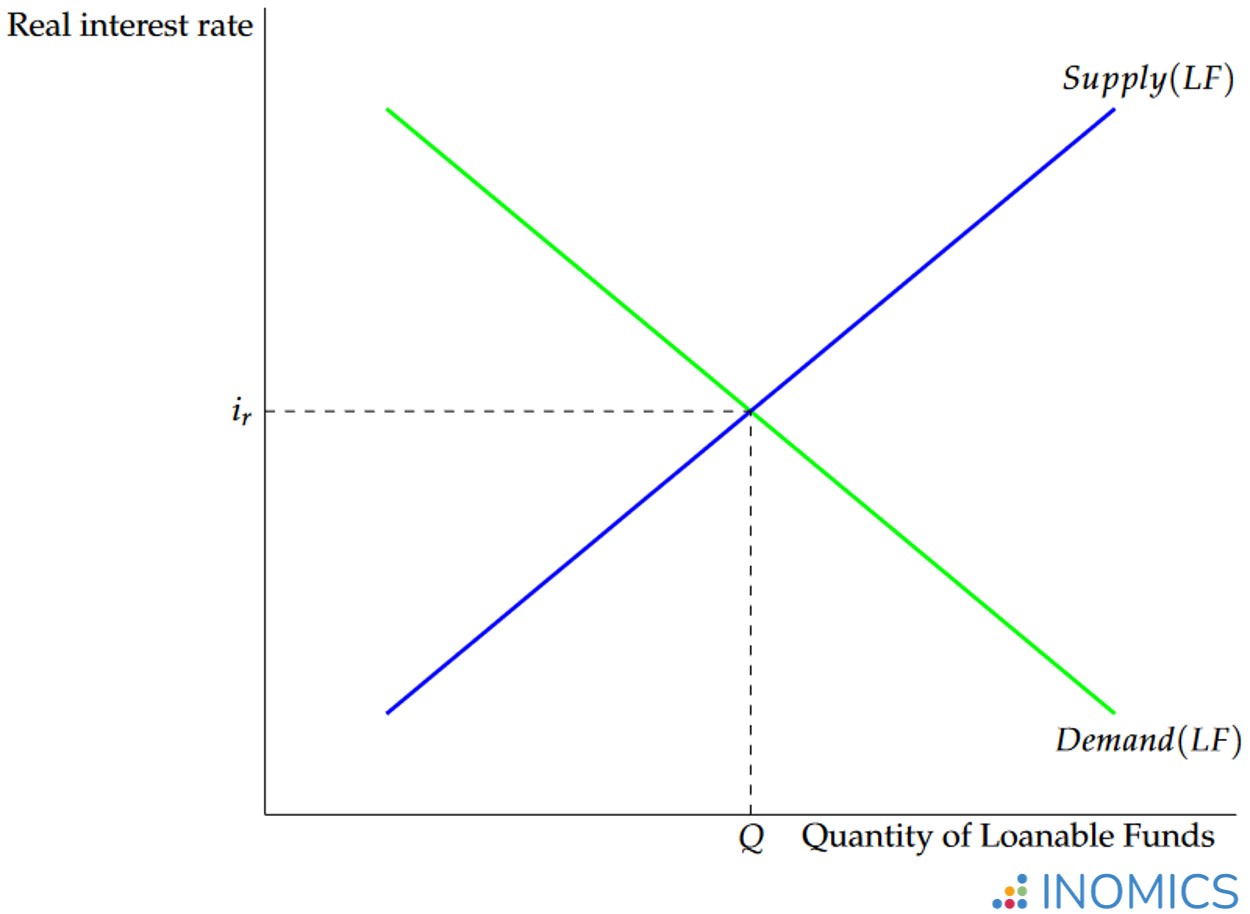

Figure 1: equilibrium in the market for loanable funds (LF)

Figure 1 shows the loanable funds market at equilibrium. First, note that the supply curve and demand curve here represent the supply and demand for loanable funds (abbreviated as LF). On the vertical axis is the real interest rate, which is the price for loanable funds. The horizontal axis shows the quantity of funds demanded and supplied.

This market works much the same as a typical market for a traditional good or service in microeconomics. Equilibrium is reached when the quantity demanded and quantity supplied for loanable funds are equal at a given price for those funds (the interest rate).

Loanable funds are an important part of the savings-investment identity in economics as well. In short, this identity states that the quantity of funds used for investment must be equal to the amount of savings in the economy. Note that this identity is always true because the funds used for a loan are repackaged from savings.

Readers may wonder if this means the LF market is always in equilibrium. That’s not the case; the LF market can be in disequilibrium. For example, a rightward shift (increase) in the demand for LF without a matching increase in the supply will eventually cause the real interest rate to rise and the quantity of loanable funds “traded” to rise. While the economy reaches the new equilibrium, the savings-investment identity still continues to hold by definition, as investors with their increased demand offer to pay higher interest rates to acquire loans for the projects they now wish to fund (or suppliers realize they can raise rates, which attracts more savers).

Shifts in the LF market

This begs the question: what causes either the supply or demand for loanable funds to shift?

Any factors that change savings or investment behavior at any given interest rate will shift the equilibrium in the market for loanable funds by shifting either the supply (savings) or demand (investment) for loanable funds. For example, the rightward shift in the demand for loanable funds above could have been caused by increased business confidence in the economy, causing firms to seek more funding for investments even though interest rates hadn’t changed.

Some factors that can shift equilibrium in the market for loanable funds include, but are not limited to:

- Increased consumer and business confidence (increasing the demand for loanable funds)

- Changing government policies that influence savings (i.e., changes to inheritance taxes, pensions)

- Introducing incentives for investing, such as subsidies or tax credits for investments (increasing the demand for loanable funds)

- Increasing economic growth (a bigger economy means more investment, ceteris paribus)

- The central bank conducting open market operations or other monetary policies (for example, the central bank can reduce the supply of loanable funds by reducing the money supply)

- Changes in the balance of international trade (for example, a trade surplus causing capital inflows increases the amount of savings in the domestic economy)

- Changes in the age distribution of the population (aging workers tend to save less for the future)

- Changing expectations of future inflation (higher expected future inflation lowers the supply of savings today, and vice-versa, as long as the Fisher Effect does not hold)

In short, the demand for loanable funds shifts when investment projects become more or less attractive even if the real interest rate hasn’t changed. Similarly, the supply of loanable funds shifts when saving money becomes more or less attractive even if the interest rate hasn’t changed.

The LF market and Aggregate Demand

Monetary policy often involves pressuring interest rates to move towards the central bank’s target interest rate. Central banks attempt to reach their target interest rate through various instruments, like buying and selling securities (“open market operations”).

Monetary policy actions also have consequences for aggregate demand. In fact, many factors that affect aggregate demand also affect the market for loanable funds. Recall that the formula for aggregate demand (or AD) is Y = C + I + G + NX, where Y stands for output, C stands for consumption spending, I stands for investment, G shows government spending, and NX represents net exports.

Factors that shift aggregate demand are factors that shift one or more of its components: C, I, G, or NX. Clearly, with investment I being a core component of the aggregate demand equation, factors that shift the supply or demand for loanable funds and cause a new equilibrium in the LF market will affect the I component of aggregate demand. This can cause shifts in aggregate demand, and therefore change the equilibrium output in the economy.

For example, suppose a newsworthy event increases businesses’ confidence in the economy for the better. In this case, businesses will increase their investment for any given interest rate as they expect the economy to perform well in the future. Thus, the demand for loanable funds shifts to the right, and the equilibrium quantity of investment I increases. This causes an increase in the I component of aggregate demand, and shifts the aggregate demand curve to the right.

Further Reading

Because of the savings-investment identity, we know that I = S where S stands for savings. Investment can be thought of as the “demand side” of this equation, while savings is the “supply side”. Therefore, changes in the amount of saving in the economy will have an effect on investment and the LF market as well.

A 1990 IMF research paper, “The Role of National Saving in the World Economy”, examines a variety of factors that influence the savings rate as it explores reasons why the savings rate has dropped over time in developed economies. Chapter II in particular examines the determinants of savings in great detail. It’s a very useful read for students interested in learning more about the behavior of saving in economics. The paper is freely available for download at the IMF’s eLibrary site.

Good to Know

When economies are not in autarky, the market for loanable funds is affected by capital flows across borders. Countries where the real interest rate is relatively high will tend to experience capital inflows (ceteris paribus), as foreign savers attempt to take advantage of the high interest rates in those economies. Meanwhile, countries with lower real interest rates will experience capital outflows as domestic savers seek better returns for their savings elsewhere.

These forces combine to pressure interest rates into an international equilibrium. Countries experiencing net capital inflows will face a downward pressure on the real interest rate, as new borrowers from abroad seek to “purchase” savings alongside domestic savers. Meanwhile, the lack of savers in low-real-interest-rate markets will cause savers in those places to demand higher rates. In turn, this will prompt banks and other institutions to raise rates in an attempt to attract more savers.

-

- Conferencia

- Posted 1 week ago

46th RSEP International Conference on Economics, Finance and Business

Between 17 Apr and 18 Apr in Paris, Francia

-

- Conferencia

- (Hybrid)

- Posted 1 week ago

2026 Asia Economics and Policy Forum ‘LIVE’

Between 28 Jul and 29 Jul in Singapore, Singapur

-

- Postdoc Job

- Posted 1 week ago

Two-year Postdoctoral Research Position in Economics

At Department of Economics and Management, University of Padua in Padova, Italia