Economics Terms A-Z

Monopoly

Read a summary or generate practice questions using the INOMICS AI tool

A monopoly in economics describes a market in which there is only one firm and it does not face any competition. A monopolist is a firm that offers a unique product or service without close substitutes and therefore does not have any competitors. This means that the monopolist has access to the entire market demand and each customer interested in buying the product can only choose whether to buy from the monopolist at the respective price or not to buy at all.

As consumers have no alternative to the monopolist's product (except not buying) the monopolist, as opposed to a firm in perfect competition, can charge a price above marginal costs. Remember that in perfect competition there are so many buyers and sellers that no one can influence the market price, and firms have to price at marginal costs.

If a firm in perfect competition decides to price above marginal costs, it will not sell anything, because the consumers have plenty of other alternatives. The lack of alternatives for the consumers in a monopolized market allows the monopolist to charge a higher price, because there will still be consumers interested in buying the good even if the price is above marginal costs.

The monopoly price

The monopolist is a profit-maximizing firm and will therefore charge a price that maximizes its profits given the market demand. How does the monopolist maximize profits?

Profits are the difference between total revenue and total costs. When the monopoly decides how many units to sell it will compare the change in total revenue from selling one additional unit, i.e., the marginal revenue, to the increase in total costs, i.e. the marginal costs of this unit. The marginal revenue of a monopolist is lower than the market price, because to sell more units the monopolist has to reduce the price for all units.

As long as the marginal revenue exceeds the marginal costs, producing one additional unit will increase total revenue more than total costs which means that the profit increases. At the unit where the marginal cost of production equals the marginal revenue from selling that unit, the monopolist will cease production. This is because beyond this point, selling more units will decrease profit.

The monopolist is able to do this because it has price-setting power. In contrast, a perfectly competitive firm (which is a price-taker) produces units until its marginal cost of production equals the set market price. If a firm in a perfectly competitive market attempted to sell units at the monopoly price (a higher price point at which marginal revenue equals marginal cost, or MR = MC), it would fail to sell any units at all. This is because consumers could simply buy from the firm’s competitors, who sell at a lower price that is equal to marginal cost P = MC.

Consequently, the monopolist maximizes its profits at the quantity where marginal costs are equal to marginal revenue (MR = MC). At this point it doesn't make sense for the monopolist to increase or to decrease the quantity.

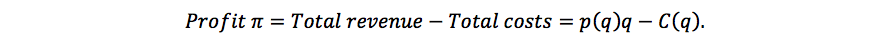

Mathematically, the monopolist maximizes profits

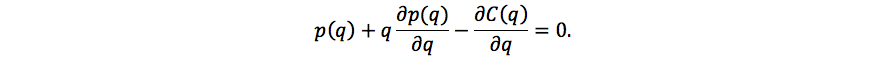

Taking the derivative with respect to quantity q and setting the derivative equal to zero, we obtain the following first-order condition:

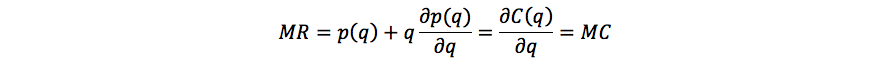

The first two terms on the left-hand side are the marginal revenue and the last term is the marginal cost of the monopolist. Therefore, we obtain the result that at the optimal quantity the marginal revenue (MR) has to be equal to the marginal costs (MC):

Let us look at a simple example. Suppose that a monopolist produces at constant marginal costs equal to 2, i.e.,

The solution for this example shows that the optimal quantity of the monopolist is equal to 3 and the price (which we find by plugging back in into the demand function) is equal to 5. For any quantity below 3, the monopolist can increase its profit by increasing production. If the quantity exceeds 3, the profits begin to decrease as the quantity increases. This is shown in the table below:

|

Price |

0 |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

|

Quantity |

8 |

7 |

6 |

5 |

4 |

3 |

2 |

1 |

0 |

|

Profit |

-16 |

-7 |

0 |

5 |

8 |

9 |

8 |

5 |

0 |

The price that the monopolist charges is higher than the market price in perfect competition (which is equal to marginal costs) and the monopoly quantity produced is lower than the quantity sold in a perfectly competitive market. This means that there are some customers who would be willing to buy the good at a price above marginal costs, but lower than the monopoly price. However, this is not possible in this monopolist’s market.

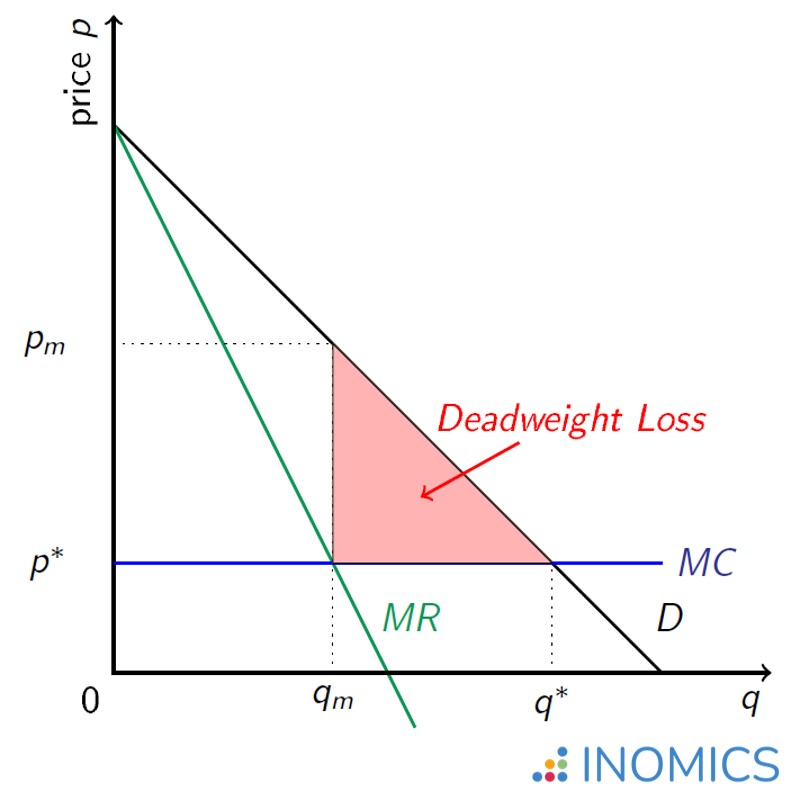

Therefore, there are unrealized gains of trade. The consumer surplus is lower than the consumer surplus in a perfectly competitive market. This loss in consumer surplus is not fully compensated by an increase in profits, which means that there is a deadweight loss.

This situation is depicted in the graph below. The deadweight loss, shown in red, is created by the failure of the market to include customers who want to buy above marginal costs but below the monopoly price. The monopoly price, pm, is the price at which marginal revenue from the next unit sold is equal to marginal cost. This produces a quantity qm that is less than the perfectly competitive quantity. If the market were perfectly competitive, the price would be p* and the amount sold would be q*.

Figure 1: Deadweight loss from a monopoly market

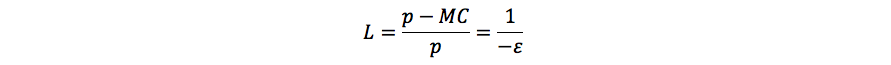

How much the monopoly price will be above marginal costs depends on the price elasticity of demand. If demand is inelastic, which means that a comparatively high increase in the price will cause a small reduction in the quantity demanded, the monopolist can charge a higher price.

In the case of an elastic demand the monopolist would lose too many customers by increasing the price and therefore has less ability to charge a high price. The possibility to charge a price above marginal costs is what we refer to when we talk about the market power of a monopoly. The market power of the monopolist can be measured by the Lerner index which is defined as

Where

Why do monopolies exist?

There are several reasons why some markets are and remain monopolized. In some markets barriers to entry make it difficult for potential competitors to enter. For example, if one company controls the access to an essential resource, competitors without access to the resource cannot compete in the market.

In some situations the government intentionally creates monopolies, as e.g. in the case of patents. A patent grants a temporary monopoly status to the patent holder; patents encourage innovation by guaranteeing that the inventor can earn high profits from the invention for a time.

Besides this type of intentional monopoly, the nature of production in an industry may be such that total costs of serving customers are lower if only one firm manages production. If this is the case we call the resulting monopoly also a natural monopoly.

An example of a natural monopoly is the utility industry. Utilities such as sewage and electricity are much more efficient if only one firm supplies them and is able to connect them to the local network. If market forces alone were allowed to run the industry, it could result in multiple redundant utilities competing with each other, which would be inefficiently expensive to set up (due to high barriers to entry). Moreover, with only one firm supplying the utility, it’s easier to maintain as there is only one network and not several.

Alternatively, because of the high barriers to entry, it’s possible that the first firm to provide the utility service would force all others out of the market and prevent their entry, resulting in monopoly prices and an inefficiently low number of people being served. Thus, governments usually regulate utility industries to ensure they do not charge monopoly prices and fail to serve all customers. Thus, natural monopolies may still be improved in an overall welfare sense if there is some regulation.

Further reading

As pointed out above, the problem with monopolies is that when the quantity exchanged in a market is lower than it would be under perfect competition, overall welfare is reduced. Therefore, governments are interested in knowing how to regulate a monopoly and reduce the resulting welfare loss.

One economist who extensively studied market power and regulation is Jean Tirole. For his work Jean Tirole won the Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel in 2014.

Good to know

Pure monopolies are rare, but there are several examples of markets with dominant firms that control a decisive part of the market share. Examples include the market for diamonds (De Beers), eyewear (Luxottica), operating systems (Microsoft), and others.

How much market power these firms have does not only depend on their market share, but also on other factors such as e.g. the price elasticity of demand in the market. Therefore, when competition authorities try to determine whether a firm is becoming too powerful and might abuse this power, they do not only take into account the market share of this firm, but rather focus on the possibility of the firm to charge a price above marginal costs.

-

- Postdoc Job

- Posted 2 weeks ago

Research Associate (Post-doc, f/m) in the fields of applied econometric and distributional analysis

At LISER (Luxembourg Institute of Socio-Economic Research) in Esch-sur-Alzette, Luxembourg

-

- PhD Program

- Posted 1 week ago

Graduate Program in Economics and Finance (GPEF) - Fully funded Ph.D. Positions

Starts 1 Sep at University of St.Gallen in Sankt Gallen, Switzerland

-

- Conference

- Posted 3 weeks ago

Industrial Policies in a Globalized and Financialized World

Between 7 May and 8 May